Where does your money go?

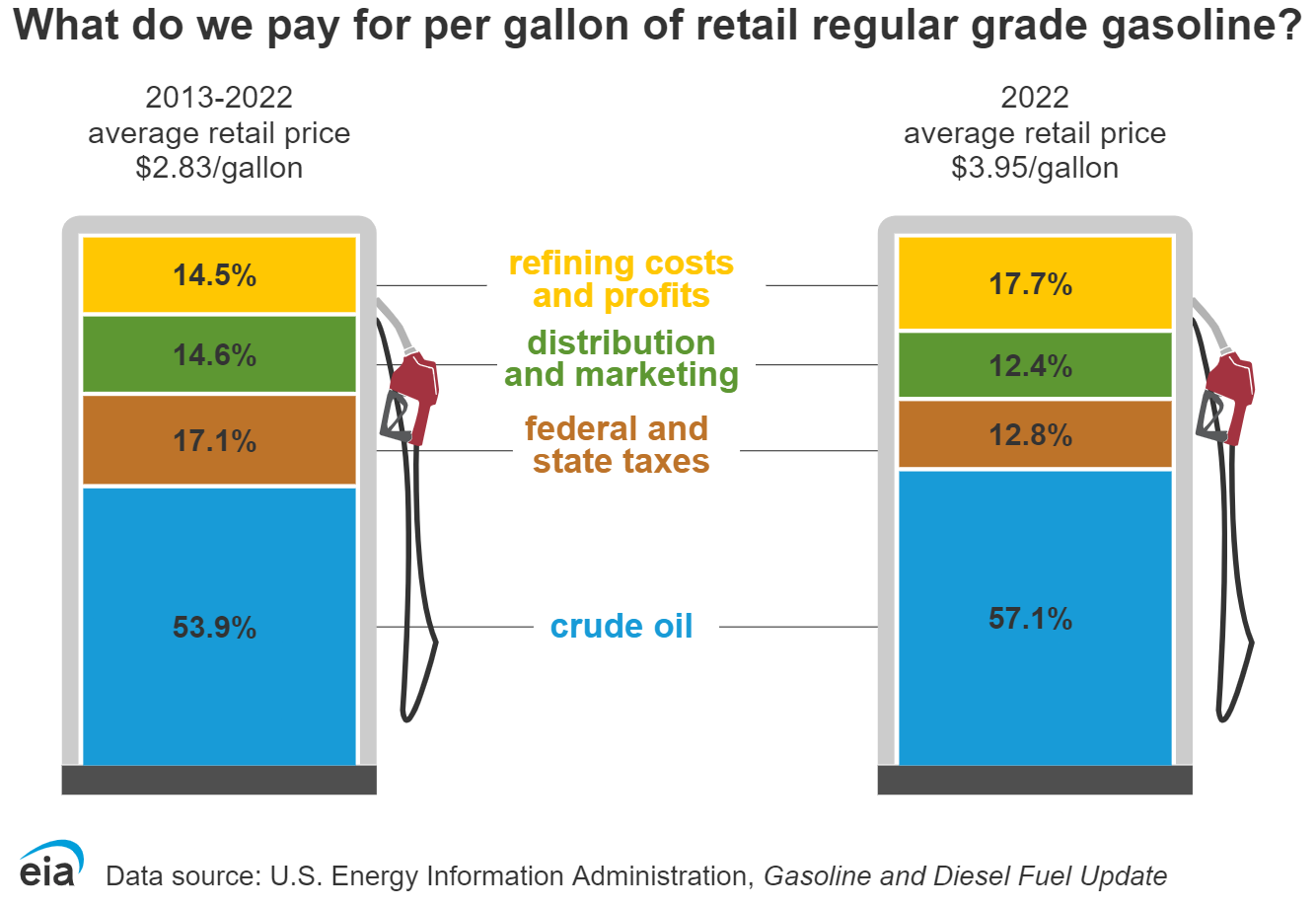

Crude Oil : The cost of crude oil is the largest component of the retail price of gasoline, and the cost of crude oil as a share of the retail gasoline price varies over time and across regions of the country. How crude is priced is very complex, but the less dependent the United Statesis on foreign sources of oil, the more stable and affordable consumer energy prices. This is why policies that would encourage and expand energy development, transportation and infrastructure are so vital.

Federal and State Taxes: Gasoline and other motor fuels are heavily taxed. The federal tax on motor gasoline is 18.40 cents per gallon. Taxes are a cost that is passed on to the consumer. Taxes are used primarily to build and maintain transportation infrastructure and as taxes rise, so do fuel prices. Sales taxes, along with local and municipal government taxes, can have a significant impact on the price of gasoline in some locations.

Refining Costs and Profit: You can’t put oil that comes out of the ground directly into your gas tank or home heating system. It needs to be converted – or refined – into fuel designed for that specific application. This process makes up around 25% of the price of fuel. However, due to strict government regulations construction of new refineries has been extremely difficult and in some cases, impossible. Refining capacity can help drive fuel prices down, so reducing burdensome regulations on maintaining and building new refineries is crucial to keep prices in check.

Distribution & Marketing: Refined fuel makes its way from refineries to distribution points and then to your local gas station. The cost of this distribution varies from station to station, and often explains regional differences in the pump price. Distribution costs and local station pricing are also affected by the Jones Act, an act passed in 1920 in an attempt to protect the US maritime industry. In addition, marketing the fuel companies makes up a portion of this cost.

Gas station prices or home heating fuel dealer’s pricing reflects the cost of the product in addition to the cost associated with operating a gas station. Operational costs can include maintaining the property, paying employees, taxes, insurance, federal and state licensing fees and so on. In order to provide the services necessary to keep stations in business, owners must pass on to their consumers an additional percent above the direct cost they pay to purchase their gas, goods and services. On average this additional cost to consumers is less than 5%. As a result the gas and home heating fuel dealer industries are among some of the least profitable industries around, and why the convenience side of the station is often so important for making the bottom line.

Why do fuel prices fluctuate?

Ever feel like you are paying too much at the pump?

From town to town, region to region, even station to station, fuel prices can differ quite a bit. As a consumer it doesn’t feel right. Sometimes it even feels unfair.

From town to town, region to region, even station to station, fuel prices can differ quite a bit. As a consumer it doesn’t feel right. Sometimes it even feels unfair.

The overwhelming majority of the 156,000 fuel stations in the US follow some fairly standard, competitive pricing strategies. It turns out, the vast majority of the time, retailers make very little on a gallon of fuel.

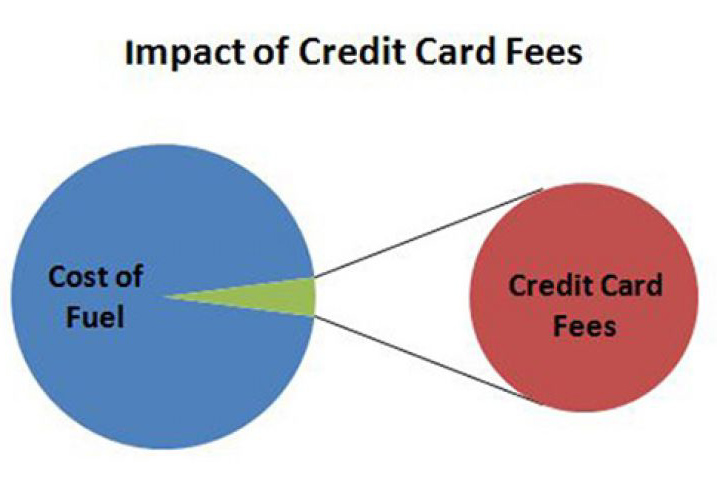

Fuel Profits: Most people are surprised to find out that gas station owners make very little on a gallon of gas. It turns out it is quite common for 8% – 10% of fuel price to be made up of marketing and distribution costs, which include, but are not limited to: franchise fees, and/or rents, wages, utilities, supplies, equipment maintenance, environmental fees, licenses, permitting fees, credit card fees, insurance, depreciation, advertising, and profit.” In other words, a gas station has to pay for all of its fuel operations out of a fraction of what you pay at the pump. After those expenses, NACS estimates gas stations make around 3 cents/gallon on fuel. Thus, if you fill up your tank with $40 of gas (at $3/gallon) the station makes a whopping $.40 on the sale. That is a 0.1% “profit margin” on what is sold at the pump. Think about that. If a retailer sells 5,000 gallons of gas a day (industry average is 4,000), they might only make a profit of only $150.

So why do stations vary? Good question. There are a ton of factors that go into fuel pricing. By far the largest factor in fuel prices is the price a station pays its distributor. When a station buys its supply and from whom directly impacts the price at the pump. As crude prices shift and affect distribution prices, fuel stations follow suit. However, there is often a timing difference between when each station gets its new fuel shipments and thus sometimes stations lag behind one another in changing their pump prices. Gasoline, diesel and home heating fuels are no different than other commodities in terms of what influences prices. Just like the fruits and vegetables at your local grocery store, the demand for certain fuels may vary from season-to-season, which affects prices. They are also influenced by many factors such as state and local taxes and production, transportation and storage costs. Healthy business competition between stations and heating fuel operators cause prices to vary and change frequently, creating the illusion of unfair pricing.

It’s all about those chips – In 2007 most of the large oil companies started selling off their fuel stations. Why? Because it is very hard to make a profit at the pump. So how do retailers stay in business? By also selling retail items. When you fuel up and go buy a bag of chips, some gum, and a fountain drink or two, the retailer may make a more reasonable profit than they do on the fuel you purchased outside. So eat up – not only is it super convenient and delicious, it also helps your small business station owner pay her employees and stay in business!

Why Shipping Regulations Increase Fuel Prices

Did you know that an obscure law passed almost 100 years ago

costs you extra money every time you fill up your tank?

The Jones Act was passed in 1920 in an attempt to protect the US maritime industry, but today it drives up the prices you pay at the pump or for your heating fuel delivery.

The Jones Act is a law that states that if you move products – including crude oil, gasoline and home heating fuels – from one American port to another, you must use American-made, flagged and operated ships. When crude is refined in the Gulf of Mexico and transported to the East Coast, for example, it may only be transported by US flagged and operated cargo ships.

The US has a limited number of cargo ships available to transport oil – only 42, in fact. When we ship oil back and forth among America’s ports, we have to rely on this small fleet to carry a LOT of fuel. There just aren’t enough ships to get the job done, and with the limited supply, transport prices go up – and consumers feel it at the gas pump. CNBC reports that the Jones Act drives up fuel pump prices in portions of the North East and South East parts of the US by as much as $.30 cents/gallon. If you live in one of these areas, that means you are paying around 10% more for fuel than necessary because of the Jones Act.

What would you do with an extra $100/year?

What would you do with an extra $100/year?